The content of this blog post was originally published as part of “Comments of T-rank on the draft Amendments to FATF Guidance on Beneficial Ownership (R.24)” in december 2022. The text has been somewhat rewritten to be understandable without this context.

Control vs Significant influence

Control is a term that usually is associated with some kind of decisive power, either by a single entity or a group of associated entities. The term is also sometimes used as a synonym for ownership in expressions such as “she controls 10% of the shares in the company”.

Most beneficial ownership definitions use terminology like “the natural persons who ultimately owns or controls the entity”. In this context, control should be regarded more as “has the ability to influence decisions” than “single handed decides everything”. In order to make such definitions more clear, T-rank proposes to change wording from “..have control” to something like “..have significant influence (on strategic decisions)”.

Unlike for cash rights, it is not at all clear how one should measure control/influence, and there exists no de facto standard way of doing it. We will first argue that “share of voting rights” (commonly used in legislation) is by no means an appropriate measure of influence. We will then propose a way to define (but not measure) the level of influence.

We will illustrate through examples that shareholders with voting rights far above usual thresholds for Beneficial Ownership can have no influence at all, and on the other hand, that shareholders having less than threshold ownership could be said to single-handedly control a company.

In this chapter, we will assume that decisions are taken by the simple majority rule, but similar examples could be created for any quota.

Example 1

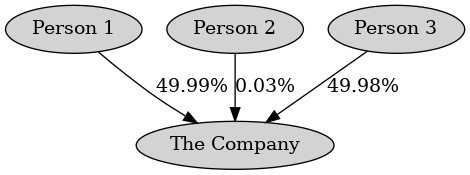

If we look at Figure 1, we see that there are three owners. In order to get majority, two of the three shareholders must vote together, but it doesn’t matter which two. It is reasonable to conclude that all shareholders have the same level of influence on the decisions to be made on a General Assembly, for instance the election of a new board of directors. Thus, if Person 1 and 3 should be considered a Beneficial Owner based on influence, so should Person 2.

Figure 1: The Company has 3 owners – none of which have a controlling majority. The labels on the arrows represent share of voting rights.

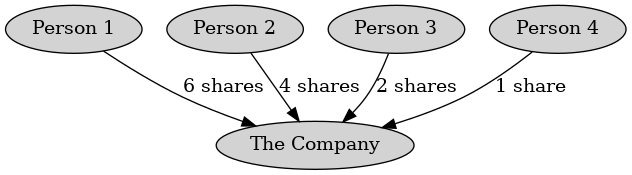

Figure 2: Largest shareholder gets majority if he colludes with any of the other shareholders.

Example 2

In Figure 2, there is a total of 13 voting rights, of which 7 is needed in order to get majority. The largest shareholder will win if he gets any of the other shareholders on his side. In order to downvote the largest shareholder, all the other 3 shareholders must vote together. From an influence point of view, it does not matter if you have 4 votes (30.77%) or 1 vote (7.69%).

Example 3

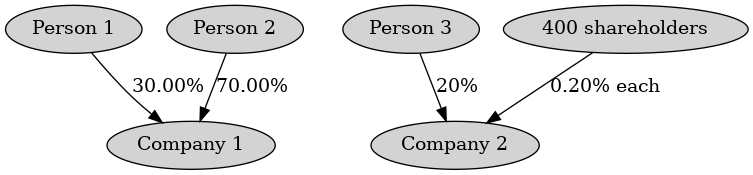

Figure 3 contains two examples. To the left, there is a 30% minority shareholder. He has no formal saying whatsoever on the decisions in the company – the 70% majority shareholder will always get her will. In the example to the right, we have one relatively large shareholder with 20% of the shares. The rest of the shares are highly dispersed among 400 shareholders. The a priori probability of the larger shareholder being pivotal for the outcome of a vote, given that all shareholders are present and all behave independently, is about 99.9999%. This last shareholder should obviously be classified as a Beneficial Owner, even though the shareholding is well below the usual 25% threshold.

Figure 3: To the left, the 30% shareholder has no influence. To the right, the 20% shareholder has ”de facto control”.

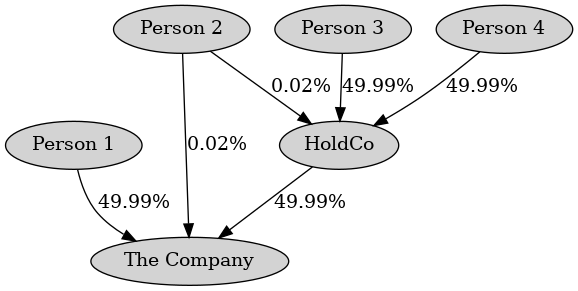

Figure 4: Person 2, even though owning only very small ownership percentages, is by far the most powerful owner.

Example 4

Figure 4 is a sort of ownership structure that can be quite often observed in real life, usually tied to generational changes in family companies. Person 2 will win any vote in The company if he can get any of the other persons on his side: If he votes together with Person 1, they will have direct majority. If he votes together with Person 3 or Person 4, they will have majority in HoldCo and thus – adding Person 2’s direct votes to HoldCo’s – majority in The Company. Person 2 is by far the most powerful owner. If the others want to downvote Person 2, they must all vote together. Person 2’s integrated ownership in The Company is about 0.03%.

Based on the examples, it is reasonable to conclude that share of voting rights is not a suitable measure for the level of influence a shareholder has in the company.

Introducing Equal Influence Level

Ideally we would like to have a measure of influence that is widely accepted and work well in most situations. Unfortunately, such a measure does not exist today. The second best thing to do is to somehow describe the level of influence that triggers Beneficial Ownership. Our proposal is to use something we call Equal Influence Level to define influence levels by example.

Definition: Assume that strategic decisions in an entity are taken by simple majority of votes among a set of n decision makers, where each decision maker acts fully independently from each of the others and each decision maker has one vote. We denote the level of influence one of the decision makers has under these conditions Equal Influence at level n, written in short as EqIL<n> where <n> is replaced by the actual value for n.

Example: Assume a foundation is governed by a 5-member board of directors, where each board member has 1 vote. A foundation has no owners – strategic decisions are taken by the board. If the board members act independently, they each have Equal Influence Level EqIL5.

Example: A limited liability company is owned by 4 owners, each having 1 share. If the owners act independently, they each have Equal Influence Level EqIL4.

Equal Influence Level is not in itself a methodology for measuring influence. It only defines a set of reference levels that could be used in definitions. Obliged entities must adopt some sort of methodology or guidelines for deciding which natural persons have sufficient influence for Beneficial Ownership. Note that the lack of measurement method is no different from the current guidelines – the difference introduced by our proposal is an objective level to compare against. In most situations, some kind of power index will be a good choice for determining Beneficial Ownership based on influence.

A quite common ownership threshold for Beneficial Ownership today is 25% + 1 share. If we assume that we create as many Beneficial Owners as possible and that we give these equal rights, we will get three shareholders having something like 25.01% each (we can forget the rest of the outstanding votes since at least two of our three 25.01% shareholders always will vote the same and thus have majority). This situation corresponds to EqIL3.

A threshold of 10% + 1 share would similarly correspond to EqIL9. However, the reason for setting such a low threshold to begin with is probably a recognition of the shortcomings of measuring influence by voting rights. If EqIL3 is found to be too relaxed, EqIL4 or EqIL5 offer more natural choices than EqIL9.

Note that the Equal Influence Level approach should work well for most entity types.

For limited liability companies, the distribution of voting rights is considered.

For entities that are not owned by anyone and where the board has all the power (trusts, foundations, organisations, ..), one would look at the number of board members. If there are 5 or less board members and EqIL5 is the defined Beneficial Owners criterion, the board members become Beneficial Owners. If there are more board members, they will not become Beneficial Owners.

For partnerships where strategic decisions are taken among all partners, the same logic applies – more partners than the Equal Influence Level will result in no Beneficial Owners, number of partners up to and including the Equal Influence Level will result in all partners becoming Beneficial Owners.

Example 5.7. Assume that we regard natural persons having influence corresponding to at least EqIL3 as Beneficial Owners. We will then get the following Beneficial Owners for Figure 1 – Figure 4:

Figure 1: There are three shareholders, all having the same influence level. This is by definition EqIL3, and they all become Beneficial Owners.

Figure 2: In this example, it is obvious that the largest shareholder becomes a Beneficial Owner based on influence whilst none of the others do. Person 2 will probably be considered a Beneficial Owner based on cash rights.

Figure 3 left example: Person 2 has full control and is thus a Beneficial Owner. Person 1 has no influence, but will with normal thresholds become Beneficial Owner because of cash rights.

Figure 3 right example: Person 3 has far more influence than EqIL3 and should be considered a Beneficial Owner.

Figure 4: Person 2 has EqIL3 even without taking his HoldCo holdings into account, and is thus Beneficial Owner based on influence. Person 1 will become Beneficial Owner based on his cash rights, while Person 2’s and Person 3’s cash rights are right below the threshold if the threshold is 25%. An important thing to notice about this example is that Person 1’s influence in The Company is (far!) less than EqIL3 even if the situation looks quite similar to Figure 1. This is caused by Person 2’s cross shareholdings.